Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and race

aeffen | Boston, MA | June 6, 2020

I'm thinking today about Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) and race. Specifically, diagnosis: How does our mental "picture" of EDS and joint hypermobility syndrome (JHS) affect who is recognized and offered care?

The Beighton score

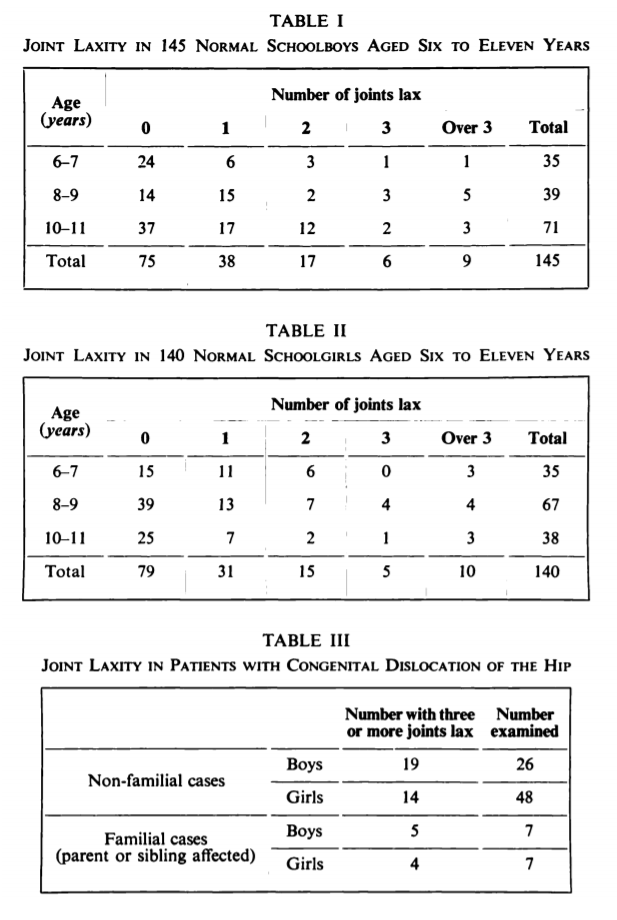

Point-based metrics for EDS diagnosis actually predate the Beighton score. In 1964, Cedric Carter and John Wilkinson published a study of 285 schoolchildren in Kent, England using 5 tests of laxity:

- Passive apposition of thumb to flexor aspect of forearm (bending your thumb forward to touch the inner surface of your forearm)

- Passive hyperextension of the fingers so they lie parallel to the extensor aspect of the forearm (bending your fingers backwards until they lie parallel to your forearm)

- Hyperextension of the elbow (bending your elbow past the "normal" range of motion where the arm is straight, to the point where your forearm bends outwards)

- Hyperextension of the knee (bending your knee past the "normal" range of motion where the leg is straight, to the point where your leg looks like it's curved backwards)

- Increased dorsiflexion of the ankle and eversion of the foot (tilting your foot upwards towards your shin, or inwards towards the midline of your body, past the "normal" range of motion)

The authors found laxity of more than 3 joints in about 7% of all schoolchildren, and they concluded that familial joint laxity was an important predisposing factor for hip dislocation in boys. They additionally referenced several animal studies and general studies of maternal hormone transfer to claim that joint laxity in girls may have a temporary hormonal explanation that lessens the importance of laxity for hip dislocation risk. However, by their own interpretation, this conclusion is rather spurious, as the maternal hormone effect should disappear shortly after birth and have no relevance to laxity observed in 6-11 year old children.

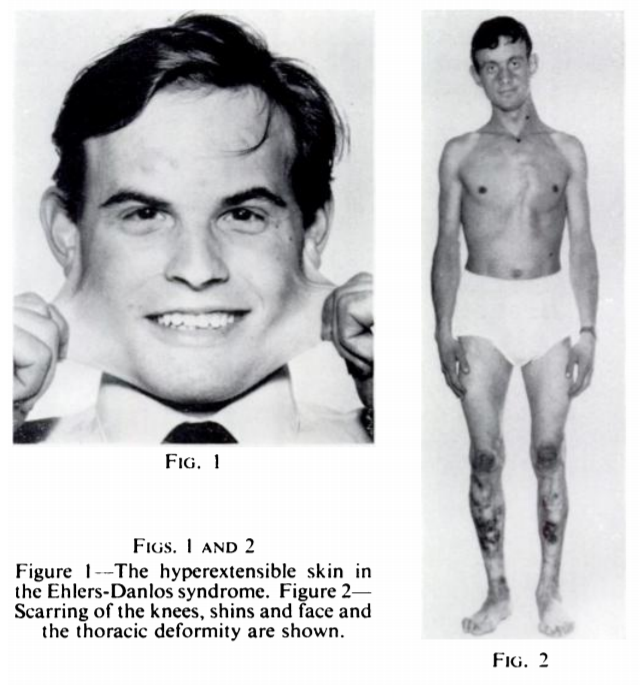

Five years later, Peter Beighton and Frank Horan published a modification of Carter and Wilkinson's 5-point score in 1969 based on a study of 100 patients in southern England. In addition to characterizing various cutaneous (skin) features of EDS, they replaced two of Carter and Wilkinson's joint laxity criteria:

- Passive apposition of thumb to flexor aspect of forearm

- Hyperextension of the elbow beyond 10 degrees

- Hyperextension of the knee beyond 10 degrees

- Passive dorsiflexion of the little finger past 90 degrees with the forearm flat on a table (bending your pinky backwards until it makes a right angle with your forearm, and going farther than that)

- Forward flexion of the trunk with hands resting easily on the floor (bending forward and put your palms flat on the floor)

Beighton and Horan's influential work would lay the groundwork for the initial classification of EDS into various subtypes, leading to the differentiation between hypermobile and vascular or other forms of the syndrome. (You can find a more thorough history of EDS classification written by Parapia and Jackson in 2008. However, these early studies were highly limited in geography and demographics.

As early studies sought to differentiate between normal mobility and hypermobility in the general population, race and ethnicity were considered, but results were mixed. R. Grahame summarized some results and contemporary papers reporting on joint mobility between different races in 1971. At this time, it was proposed that joint laxity could be associated with increased risk of joint-related trauma, effusion, and premature osteoarthritis. However, the demographic and epidemiological features of EDS and JHS remained murky.

Finally, Beighton et al. published the 9-point score we know and use today in a 1973 study conducted in Phokeng, South Africa. Their manuscript mentioned briefly that non-Caucasian populations were thought to have greater joint hypermobility on average, but the study itself was not comparative.

Prevalence and diagnosis today

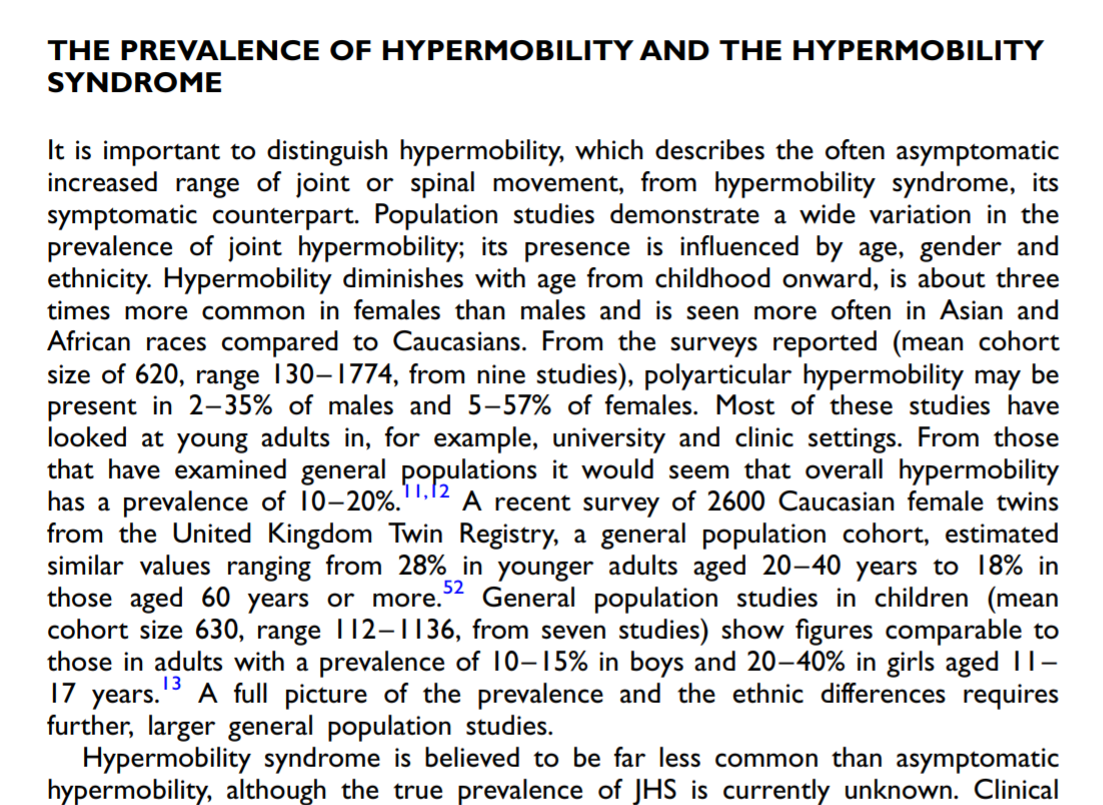

While sex has been reproducibly shown to influence Beighton score, and thus diagnosis of EDS, JHS, or general joint hypermobility (GJH), results on race/ethnicity are conflicting. Some studies:

Hakim & Grahame 2003: "asymptomatic" hypermobility is more common in "Asian and African races" but prevalence of hypermobility syndrome (~synonymous with clinical diagnosis) is unknown

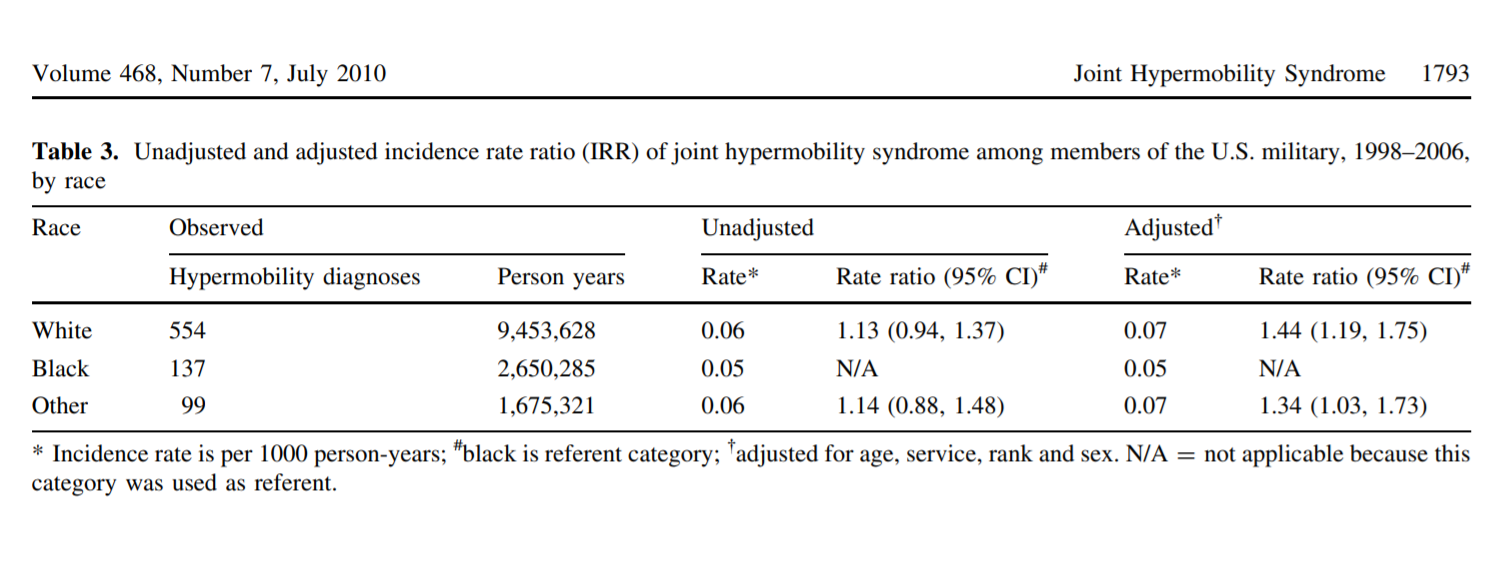

Scher et al. 2010: White military service members slightly more likely to have JHS code information (~clinical diagnosis) on file

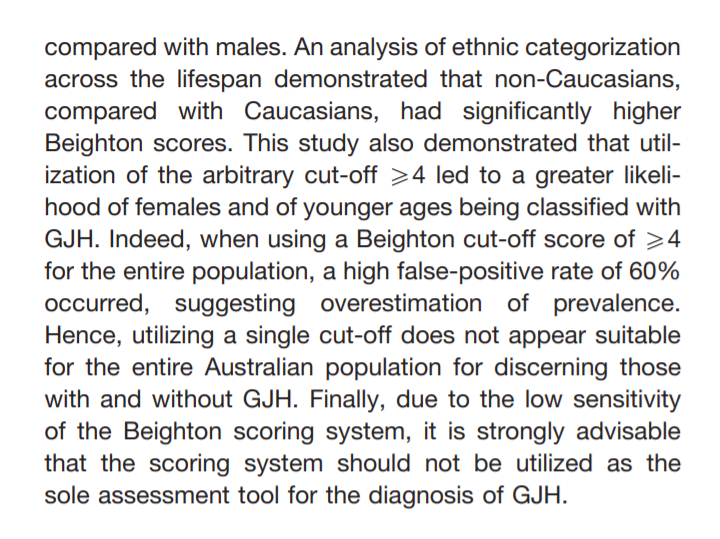

Singh et al. 2017: in normal healthy population, non-Caucasian Australians have higher Beighton score over lifespan, so universal cutoff may be unsuitable

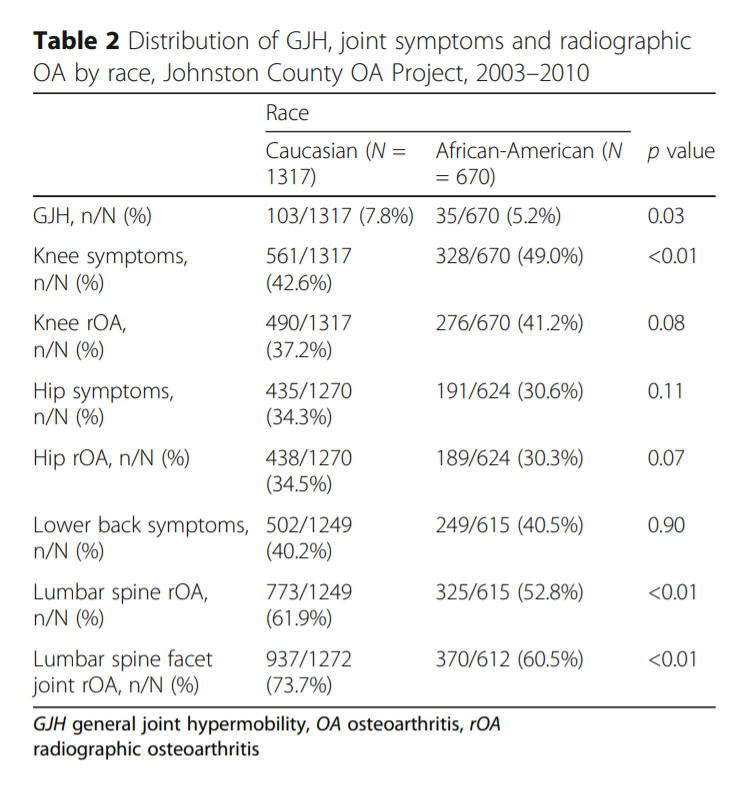

Flowers et al. 2018: GJH defined as Beighton >=4 more common in Caucasians, and frequency of reported symptom types differ by race

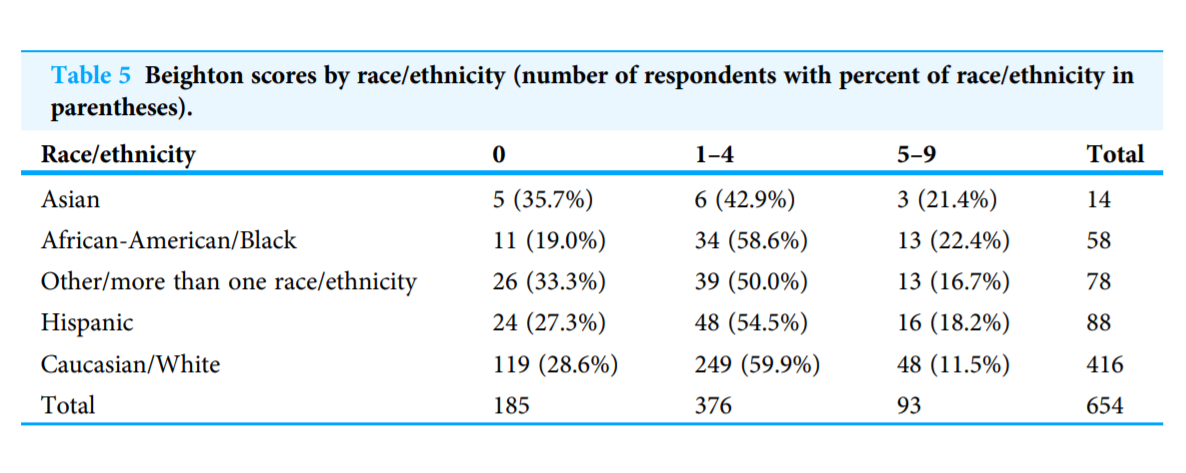

Reuter & Fichthorn 2019: Pre-health students at a university in the US show no significant difference by ethnicity in GJH prevalence based on survey and peer assessment on Beighton criteria with goniometer

We know that EDS and JHS are extremely complex and influenced not only by genetics but environment. Life experiences, profession, and medical history (such as incidence and frequency of physical trauma) all affect how the disease manifests. Furthermore, an official diagnosis crucially depends on whether or not a patient has access to a physician who listens and sees that something is wrong. This can be particularly troublesome when joint pain is often the core symptom that prompts a patient to seek medical attention, because pain is systematically discounted for Black patients. This phenomenon is well-documented (e.g. Hoffman et al. 2016). Even with a diagnosis, non-white patients diagnosed with one or more musculoskeletal conditions are less likely to receive physical therapy (Carter & Rizzo 2007). Moreover, as many know, the medical establishment still fails many with EDS who seek and receive therapy (Bovet et al. 2016).

The problem becomes multilayered. If the picture of "someone with EDS" is still a white woman, will doctors even consider EDS in the differential diagnosis for people outside of that image? How many Black kids had symptoms like me but never got referred to the right specialist? If we can't reliably diagnose EDS for Black patients, how can we even try to estimate its prevalence? If Black people are systematically less likely to be referred to therapy services, how can we design interventions that will actually make a difference for everyone with EDS? There is no neat answer to finish this post. Only questions: how can we do better as patients raising awareness for the full community of people with EDS? How can doctors, researchers, and allies take EDS more seriously for everyone, especially Black people and other marginalized identities who are systematically discounted and mistreated by medical systems?